What do we mean by distancing?

Distancing ourselves from the climate crisis means giving ourselves a break from thinking about it, engaging with it or our feelings about it.

Distancing happens in different ways including self-care and denial or avoidance. It might be something we choose to do deliberately, for example, by making room in our lives for rest and fun, or we might not be aware we’re doing it.

Distancing can give us some relief from the strong emotions, worries and stress of thinking about and engaging with the crisis. It also makes space for all the things we to live a good life, like our paid or domestic work, hobbies, relationships etc.

Helpful distancing supports us in our aim of learning to cope and adapt. More problematic kinds of distancing, may be helpful in the moment, but they get in the way of long term adapting and transforming1 Adjustment and transformation is our long-term goal. We need to change ourselves and make changes in the way we act individually and collectively if we’re to: a) get to a point where living with the climate crisis and responding to it is integrated into our everyday lives, and b) stop the crisis from getting worse than it already is. that might allow us to enjoy our lives, cope with what’s coming and take action that tackles the causes of the crisis. Sometimes distancing results in rejecting the information altogether and denying that climate change is happening. This is understandable but denial doesn’t allow you to take action or come to terms with what’s happening. Meanwhile, the climate crisis continues to develop whether we believe in it or not.

The difference between helpful and problematic distancing is not straightforward. What might cause problems for one person in one situation might be necessary at another time or for a different person. For example, climate denial, when someone insists climate change isn’t anything to do with them, or even that it’s happening at all, might seem to be a clear case of a problem response. However, temporary denial might be useful. A period of denial might give someone space to deal with an immediate issue in their life, or to avert mental health issues like burnout.

In Panu Pihkala’s model 2Pihkala, Panu. “The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal.” Sustainability 14, no. 24 (January 2022): 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628. of our journey through the crisis, people move from mostly distancing to self-care as they learn to live in the crisis. But the need to get distance from the crisis never goes away.

Distancing is one of the essential components of healthy coping in Dr Panu Pihkala’s model. Without it, we might be risking despair or burnout.

Some examples

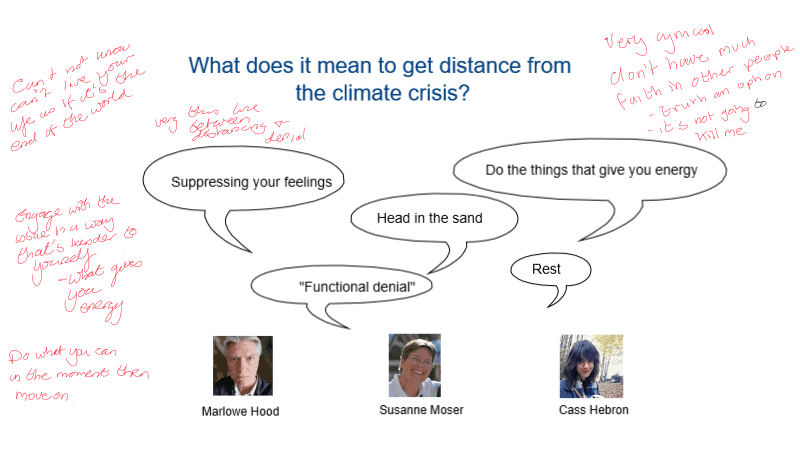

Before we start thinking about our own experience I’m going to share the stories of three people who’ve written about the difficulties they had living with really understanding what the climate crisis means. These examples make it easier to understand what it means to distance yourself from the crisis and why it’s important. The first comes from a journalist who writes about the climate crisis, the second from an activist and the third from a scientist.

The journalist Marlowe Hood 3Hood, Marlowe. “Watching the World Burn.” Correspondent, September 5, 2022. https://correspondent.afp.com/watching-world-burn.

- He experienced an “oh shit moment” in 2009.

- He had read lots of science but it wasn’t until then, at a conference in Oxford, that he was hit by the “knee-buckling” realisation that if it was left unchecked, climate change would be civilisation ending.4Hood, Marlowe. “Watching the World Burn.” Correspondent, September 5, 2022. https://correspondent.afp.com/watching-world-burn.

- From then on he was unable to not see it. He was working every day with scientific reports and stories on climate change.

- His colleagues complained his reporting should be more optimistic.

- He kept working, but rarely let himself relive that “oh shit” moment, and the emotional intensity.

- After 12 years he finds himself losing the ability to shut down his feelings and recognises he’s had symptoms of anxiety for some time.

The Activist Cass Hebron 5Dread, Gen, and Cass Hebron. “When the Nonstop Urgency of Climate Work Collides with Your Body Begging for Rest.” Substack newsletter. Gen Dread (blog), March 14, 2024. https://gendread.substack.com/p/when-the-nonstop-urgency-of-climate.

Cass Hebron was a 25-year-old activist working on climate policy in Brussels.

- She experienced burnout that meant she had to take leave from her job.

- She says her body was telling her to stop but she was “like, nah, it’s not a convenient time.

- She says her time off wasn’t very productive, and she had to go back to work because when you don’t have money “it’s not rest it’s just stressing”.

- She says you need structured support for burnout – you need to do the things that bring you energy”

The climate scientist Susanne Moser 6Mazur. “Despairing about the Climate Crisis? Read This.,” 2019. https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/articles/entry/despairing-about-climate-crisis/.]

- Susanne Moser is a climate scientist working in science communication.

- She says:

There are two reactions we have to a threat: we either deal with the threat, or we deal with the feeling about the threat.

Susanne Moser

The first option actually reduces the threat. You reduce it, you run away from it, or you build a seawall against it. The other one is, I don’t want to look this awful issue in the face because I don’t know what to do. So I’m going to stick my head in the sand.

- Susanne Moser has a strategy for staying aware of the truth about the severity of the crisis and carrying on with everyday life. She calls it ‘functional denial’. She says “The denial part is what we all have. It is incredibly hard to look the realities we have created in the eye. The functional part is that we have to keep going regardless.”

- She says that day to day she functions as if it was the same old world – doing the things that have to be done like work, paying bills, taking care of her family and so on. But she also at the same time, every day she’s facing the reality of the crisis. Functional denial is about staying fully aware of what’s happening and living a normal life simultaneously.

Summary

So, we have four versions of distancing in these stories:

- Suppress your feelings

- Rest and do the things that bring you energy

- Denial, “head in the sand”

- Simultaneously doing normal stuff as if everything was the same, but also facing up to the crisis.

Our Conversation

- We can’t not know. But also, you can’t live your life as if it’s the end of the world.

- There’s a very thin line between distancing and denial.

- Engage with the issue in a way that’s kinder to yourself. Like Cass says “what gives you energy”7Dread, Gen, and Cass Hebron. “When the Nonstop Urgency of Climate Work Collides with Your Body Begging for Rest.” Substack newsletter. Gen Dread (blog), March 14, 2024. https://gendread.substack.com/p/when-the-nonstop-urgency-of-climate..

- Do what you can in the moment (to have an impact on the crisis) then move on.

- I’m very cynical. I don’t have much faith in other people. Truth seems to be an option now. Climate change is unlikely to kill me.

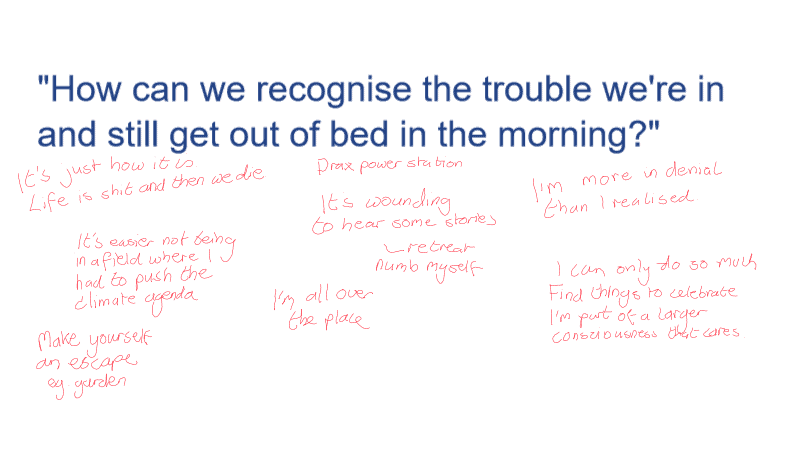

- It’s just how it is. Life is shit and then we die.

- It’s wounding to hear some stories, for example, the Panorama documentary about Drax power station8https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-63089348.

- I retreat, I numb myself.

- I’m all over the place.

- I’m more in denial than I realised.

- It’s easier not working in a field where I have to push the climate agenda.

- Make yourself and escape, for example, making a hedgehog house in the garden.

- I can only do so much. I find things to celebrate. I’m part of a larger consciousness that cares about the climate crisis.